On this day in history, 489 years ago today, the Constable of the Tower came for her. She was still likely only 35, with olive skin, a pointed face, and a long neck. She had rarely been described as a great beauty, her two main physical attractions being her long, dark-brown hair and bewitching black eyes. But everyone who knew her agreed on her endless charm and fierce intelligence. Anne Boleyn, until only two days earlier, Queen of England, had been imprisoned in the Tower of London for two-and-a-half weeks, on the orders of her former husband King Henry VIII. She had languished there, her mood fluctuating wildly as she struggled, and eventually accepted, such a bewildering and cruel change of fortune.

The “Hever Rose” Portrait of Anne Boleyn – Hever Castle, c. 1550, copy of a lost original

She lived like a queen still – by one estimate, her upkeep had cost William Kingston, Constable of the Tower around £14,627 (around $19,582) in modern currency. She had stayed in the rooms which now made up her prison for a few nights before her coronation just under three years earlier. Kingston reported to Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, that when he had told her of this detail, Anne had cried out, “It is too good for me! Jesu, have mercy on me!”, before kneeling down and weeping. Soon, those tears dissolved into hysterical laughter.

Throughout this post, I will pepper in on-screen depictions of Anne’s arrest, trial, and execution to give a better sense of how her fall has been remembered. In chronological order, from top-bottom, left-right, the actresses are Genevieve Bujold in Anne of the Thousand Days (1969), Dorothy Tutin in The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970), and Natalie Dormer in The Tudors (2007-2011).

The sobs and mirth had coexisted in a tense, uneasy amalgam of emotions, ever since May 2, when she had been summoned to the council chamber of Greenwich Palace. There, three privy councillors, including her own uncle Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, had accused Anne of adultery with three men: her husband’s close confidante Henry Norris, the court musician Mark Smeaton, and one more, as of yet unnamed, man. She had denied the charges vehemently, and with good cause, given that nearly all modern historians have concluded her innocence on each one. But her avowals of innocence made no difference. Forbidden from taking any of her ladies-in-waiting with her or saying farewell to her only surviving child, the Princess Elizabeth, Anne had soon been escorted by barge to the Tower, accompanied by her uncle Norfolk, the Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley, Cromwell, and others. This too, had been a grotesque parody of her coronation festivities, a horrible inversion of the river pageant where she had sailed to the Tower a few days before her coronation. Then, the river was alive with lively music and the noise of fireworks. Curious crowds had lined the riverbank to see the woman who’d so bewitched their king that he had not only sought to divorce his long-serving (and long-suffering) wife, the Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon, and broke with the Papacy, but succeeded. Now, the crowds regathered; this time, it was to watch, and perhaps jeer, at their queen, slandered as an insatiable adulteress and harlot.

Since then, the charges had broadened and become ever more complex, as Cromwell and Henry’s ministers embroidered ever more fantastic lies about Anne. She had not only committed adultery with Henry’s close friend and a mere court musician, but she had brazenly cuckolded the king with two more courtiers! In her lust, she had committed incest with her own brother, George Boleyn, Lord Rochford! She had even plotted with her lovers to murder Henry, playing them off against each other, as if all the temptresses of scripture and classical antiquity had melded into one. Never mind that barely a shred of proof was presented, no witnesses were called, or that the only man to plead guilty was strongly suspected of having been tortured at Cromwell’s house. They were all found guilty by a carefully selected jury. On May 12, the four men – Henry Norris, William Brereton, Sir Francis Weston, and Mark Smeaton – had been found guilty. One of their judges was Sir Thomas Boleyn, Anne’s father, whose desperate urge to survive drove him to condemn them too, thus implicitly condemning his own daughter to death. Three days later, Anne had been tried, followed by George. They had both been brave, easily ripping apart the farrago of lies which Cromwell and the prosecutors had cobbled together.

Anne’s trial on-screen, featuring, from left to right, top to bottom, Genevieve Bujold, Dorothy Tutin, Helena Bonham Carter in Henry VIII (2003), Natalie Portman in The Other Boleyn Girl (2008), Claire Foy in Wolf Hall (2015), and Jodie Turner-Smith in Anne Boleyn (2021). I am not apologizing for featuring Jodie; racists, leave now.

But it was no use. For some time now, Henry had wanted her not just gone from his life, but from this world. Exactly when is a topic of fierce debate among historians, but Anne’s position had been seriously weakened since January 29 that year, when she had miscarried. It was widely reported to be a boy. In Henry’s eyes, Anne had, for the third time, failed to give him a boy – just a girl, a stillborn child, and now a miscarriage. In my view, over the course of the spring of 1536, Henry had decided to annul his marriage to Anne, and eventually, to have her executed. Besides her “failure” to provide him with a son, which he may have seen as a betrayal of his wishes, and thus treason, her sparkling wit, fiery temper, and bewitching nature, now grated on him. He had fallen for one of her ladies-in-waiting, the pale, quiet, seemingly meek Jane Seymour. At 44 years old, well into middle age, he still had no son and heir to succeed him as king and ensure England’s security. And Anne, who was probably 34-35 at a time when women often entered menopause earlier than now, looked increasingly unlikely to give him a son.

Portraits of Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, and Jane Seymour as they would have appeared in 1536; these works are respectively in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, Nidd Hall in North Yorkshire, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Disastrously, Anne had also fallen out with Cromwell over how to best use the funds from dissolved monasteries, exacerbating a long-standing feud. By the time Henry sought to get rid of Anne, therefore, Cromwell had become convinced that his survival depended on her death. At some point, I believe that Henry and Cromwell’s initially separate plans to kill Anne merged, as the king co-opted his minister and ordered him to arrange for Anne’s fall. Little wonder, then, that both Anne and George had been found guilty and been sentenced to death; in Anne’s case, she had been condemned to be burned or beheaded at the king’s pleasure. Two days later, George and the other four men were beheaded on Tower Hill. Her grief was further compounded by the annulment of her marriage to Henry that same day by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, making her daughter Elizabeth illegitimate.

An engraving by the Victorian artist George Cruikshank of the 1553 execution of the Duke of Northumberland on Tower Hill.

Henry, in his twisted version of mercy, had already decided that Anne would be beheaded not with a clumsy axe, but a more elegant sword. He had sent for an expert French swordsman before Anne’s trial (one of the clearest proofs of her innocence), but by May 18, he had still not arrived. Anne, who had been under the impression that she would die that day and busied herself praying with her almoner since 2 A.M., had summoned Kingston while she heard Mass. Twice swearing on the Eucharist, the bread and wine that nearly every English person believed transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ, Anne once more swore her innocence. But they had not come for her shortly after 8 A.M., as she had expected. Once more, she summoned Kingston, saying, “Master Kingston, I hear say I shall not die afore noon, and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought then to be dead and past my pain.” Her jailor, hoping to console her in his own clumsy way, replied, “It should be no pain, it is so subtle.” Anne then said, “I heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck.” She then put her hands about her throat and started “laughing heartily”.

“I heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck.” Claire Foy

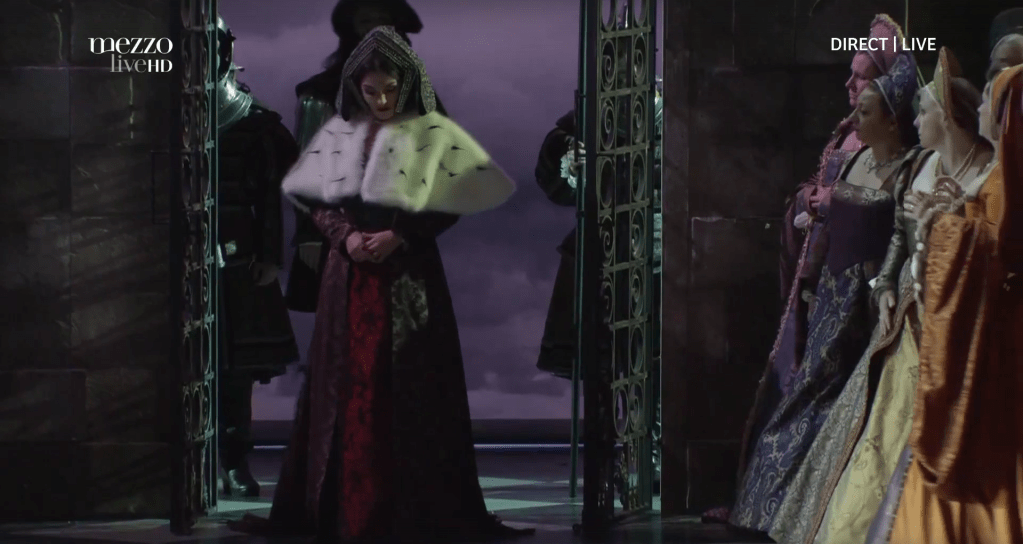

So it is that I return to where this post started. At dawn on Friday, May 19, 1536, Kingston returned to Anne’s rooms in the royal apartments of the Tower and informed her she would die that morning. When he visited a second time and told her to prepare herself, the contemporary writer Lancelot de Carle, who wrote a narrative poem of her life and fall a few weeks later, reported that she told himself to “attend to fulfilling his charge and duty”. For some time now, “God had wished to provide for her / By giving her the courage and strength / To withstand the greatest cruelty.” He gave Anne a purse of £20 (around £12,177/$16,292 in modern currency) to give in alms to the poor. She was dressed, as always, to perfection. She wore a dark gray damask gown, its low neckline baring her neck for the swordsman. According to at least two reports, she wore a crimson kirtle (petticoat), a color that, perhaps not coincidentally, was the Catholic color of martyrdom, a pointed nod to her innocence. Around her shoulders was draped an ermine mantle, its royal connotations clear to all present. And over the white coif under which she had tucked her hair, she donned a pointed gable hood, which covered her hair completely. If she had been known as an ardent Francophile in life, Anne was determined to die with an English headdress. Her dress sent a clear message: she would die Queen of England, and she would die innocent.

Anne’s execution gown, as recreated in the 2019 Royal Opera of Wallonia production of Anna Bolena, starring Olga Peretyatko as Anne.

She did not have to walk far. Accompanied by the four ladies assigned to her upon her imprisonment, she walked down the stairs of the queen’s apartments and out into a May morning. Anne and her ladies, escorted by Kingston, passed under the imposing (and now demolished) Cole Harbour Gate, the small procession making its way along the west of the White Tower. According to at least two accounts (one Imperial, one Spanish), she looked dazed and continually looked behind her. Was she, even now, hoping against hope for a reprieve? We will never know. It is, of course, possible that she did look dazed; she would not have slept much over the last few days. But every other source remarks on her composure, her self-possession, and even, as we shall see, some smiles. De Carle, who if not an eyewitness himself, would have known people who were, wrote that “never before did she seem so beautiful”. Then, finally, she saw it. The scaffold stood on Tower Green, almost certainly in front of the modern Jewel House which houses the Crown Jewels, rather than the site in front of the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula now marked by a glass monument. It was likely draped in black; if it was, one wonders whether she would have been reminded of the shroud that would soon drape her.

A 1597 plan of the Tower of London, with a red line added by me showing Anne’s last walk. The red line starts at the royal apartments of the Tower, making its way through the Cole Harbour Gate (the small X in the original map) and ending at the scaffold, built on the modern parade ground before the Waterloo Barracks (marked X in black by me).

It was now nearly 9 A.M., and as Anne approached the scaffold, she would have begun to take in the sheer amount of people who had assembled to watch her die. She was to die a private death on Tower Green, inside the walls of the Tower, but it was a relative, distinctly Tudor sort of privacy. One of Cromwell’s servants would later write that 1,000 people had gathered. We know that among them were the Mayor and Aldermen of London, the leaders of the livery companies, along with their wives, members of the House of Lords, and most of Henry’s privy counselors. Anne would have recognized several familiar faces: her 17 year-old stepson, Henry’s illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, Lord Chancellor Audley, her enemy Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Cromwell, the man who had helped bring Henry down.

Anne’s last walk to the scaffold. Amy James-Kelly, her back to the camera, is in the bottom right; she portrayed Anne in Blood, Sex, and Royalty (2022).

When she reached the top of the scaffold, she asked Kingston for permission to address the crowd, reassuring him that she would say nothing objectionable. There was an etiquette for executions and last speeches in the sixteenth century. The condemned was expected to ask for forgiveness, confess their sins, declare their faith in God, ask their audience to pray for them, and above all, praise the king and his justice. Anne had been notorious for her fiery temper. The words of her speech must have thus come as a pleasant surprise to him. While nearly every account of Anne’s death has her say something different, the substance of most is the same. Most modern accounts have used the speech found in Edward Hall’s Chronicle, a convention which I will follow here.

In an initially soft voice which gained strength as she went on, Anne declared, “Good Christian people, I am come hither to die. For according to the law, and by the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I am come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of that whereof I am accused and condemned to die. But I pray God save the king and send him long to reign over you, for a gentler, nor a more merciful prince was there never. And to me, he was ever a good, a gentle, and sovereign lord. And if any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best. And thus I take my leave of the world, and of you all, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me. O Lord, have mercy on me, to God I commend my soul.” She said all of this, according to the chronicler Charles Wriothesley, with “a goodly smiling countenance”. What seemed on the surface like an acceptance of her death and praise of the king, however, was anything but. Word of her speech, which had pointedly refused to acknowledge any sin or guilt, soon filtered out. One of Cromwell’s agents later wrote, in a missive preserved in the Lisle Letters, that “the late queen suffered this day in the Tower and died boldly.”

Anne’s last speech. Amy James-Kelly is in the bottom right.

Her speech done, Anne turned to her ladies, who carefully removed her ermine mantle. They were now in tears, a far cry from how they had taunted and spied on her initially. She took off her gable hood herself, making sure her hair had not slipped out from its coif. Then, she said farewell to her ladies, comforting them and asking for their prayers. The executioner, who de Carle describes as “distraught / And troubled by the execution”, begged her forgiveness, which she granted. Then, Anne paid him and knelt, taking care to fasten her gown about her feet, ensuring that her legs would not be visible if her skirts moved at her death. One of her ladies blindfolded her, as she prayed over and over, “To Christ I commend my soul! Jesu, receive my soul!”

Anne’s world was now black, reduced to a quiet soundscape. Legend has it that she kept looking behind her, as if to deduce by any sound made where her death would come from. To ensure the right position for his blade, the swordsman is supposed to have turned to the other side and cried out for his sword. Thinking that he would come from there, Anne turned her head. Swiftly, he crept up behind her from the other side. There is no contemporary account which confirms this, but it is not impossible nor indeed implausible. However it happened, the result was the same. The executioner swung his sword and cut Anne’s head off with a single blow. John Spelman, a judge who was present, wrote that the swordsman “did his office very well … the head fell to the ground with her lips moving and her eyes moving”, while a French source recorded that he had struck “before you could say a paternoster [Lord’s Prayer]”.

On-screen and artistic depictions of Anne’s death. Note that very few of the artwork is accurate; perhaps the most accurate is the left piece in the middle row.

As her head fell to the ground, one of her weeping ladies threw a linen cloth over it, while the others wrapped her corpse in a sheet. As the crowd dispersed, they carried Anne’s head and body a short distance to the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. Her rich clothes were stripped off, before, according to one later report, she was placed in an elm chest which originally contained bow staves meant for Ireland. If this is true, Henry, who had been so meticulous in arranging her trial and sending for the swordsman, had not bothered to provide a coffin for the woman he had first loved so ardently and then despised so virulently. At noon, she was buried without ceremony in an unmarked grave. Just a day later, Henry got engaged to Jane Seymour. Ten days later, on May 30, 1536, they were married.

Anne’s grave in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. Her bones were rediscovered during renovations in 1876 and reinterred beneath this marker.

Eric Ives called Anne “the most influential and important queen consort” England ever had. It is hard to disagree. Her memory lives on nearly five centuries after her tragic end, and she has been depicted in countless books, plays, movies, TV shows, operas, and even musicals. Not only was she a catalyst for Henry’s break with Rome, but she promoted the cause of evangelical reform and English Bibles in the Henrician Reformation. She pushed for further reform of the English Church as directed by the king, promoted preaching based on the Bible, and looked skeptically on many facets of traditional religion, like relics and monasteries. And, perhaps most famously, she was the mother of one of England’s greatest monarchs: Elizabeth I. Anne’s name remained unspoken, her existence unacknowledged in polite society, for the rest of Henry’s reign.

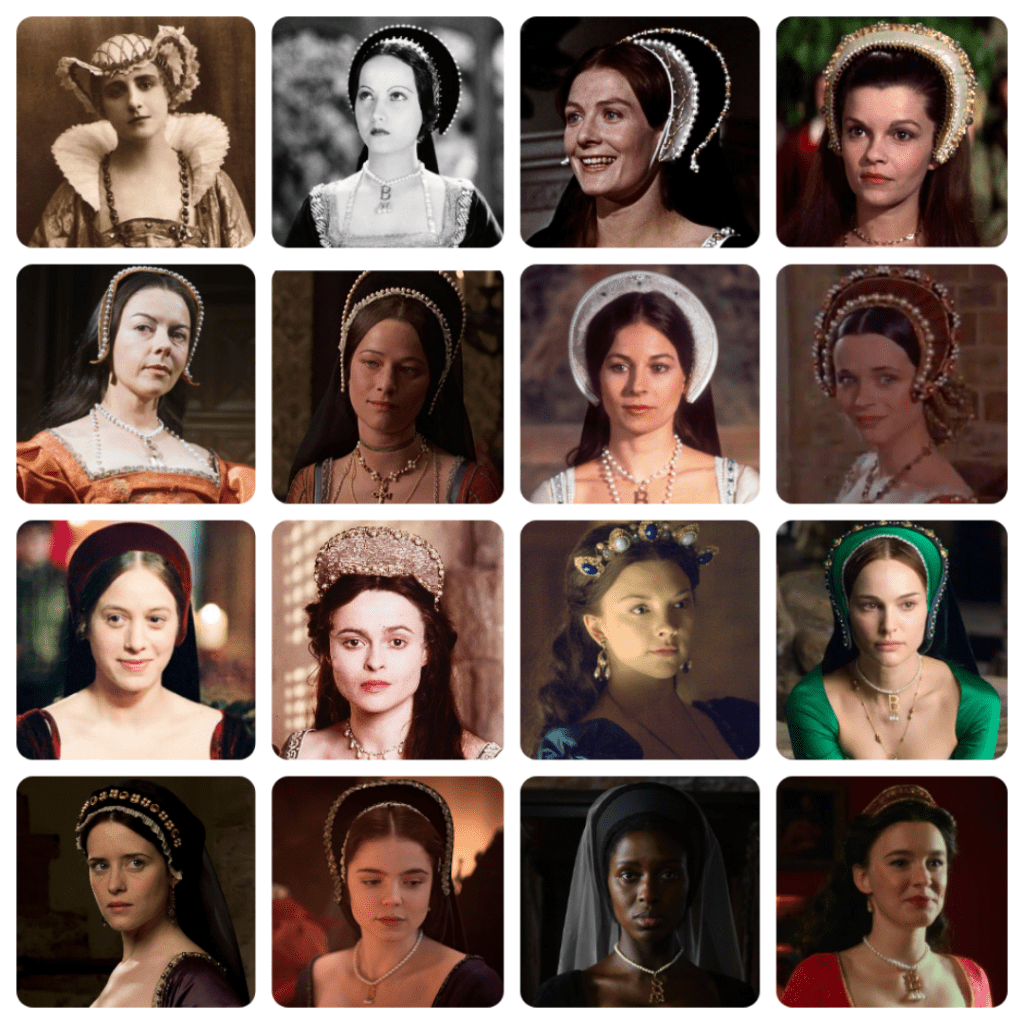

Sixteen on-screen depictions of Anne. From left to right, top to bottom, they are Henny Porten in Anna Boleyn (1920), Merle Oberon in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), Vanessa Redgrave in A Man for All Seasons (1966), Genevieve Bujold, Dorothy Tutin, Charlotte Rampling in Henry VIII and His Six Wives (1972), Barbara Kellerman in Henry VIII (1979), Oona Kirsch in God’s Outlaw (1986), Jodhi May in The Other Boleyn Girl (2003), Helena Bonham-Carter, Natalie Dormer, Natalie Portman, Claire Foy, Alice Nokes in The Spanish Princess (2019-2020), Jodie Turner-Smith, and Amy James-Kelly.

But as Kate McCaffrey and Professor Tracy Borman, OBE have made abundantly clear, Anne’s memory was cherished by many of her female friends and relatives, particularly her daughter Elizabeth. And as Elizabeth rode into London for her own coronation procession over twelve years later, she would have glanced up at the first pageant. On the first floor of its triumphal arch stood actors playing her paternal grandparents King Henry VII and Queen Elizabeth of York, the founders of the Tudor dynasty. And above them, on the second floor, was her father Henry VIII. Beside her stood the woman he had killed and whose memory he had sought so hard to destroy: her mother, Queen Anne Boleyn. At last, Anne’s reputation had been publicly rehabilitated. She was still a controversial, divisive figure, as she still is today. But for every person who dislikes or hates her, I would wager that at least two people are sympathetic to her. I am one of them; in fact, I readily acknowledge that I’m a fan of Anne. Today, I celebrate the life of an extraordinary, brilliant woman, devoted to her daughter and faith and full of courage, intelligence, and spirit, who permanently changed the course of history. Rest in peace, Queen Anne Boleyn. Your astonishing life, tragic fall, and monumental legacy will never be forgotten.

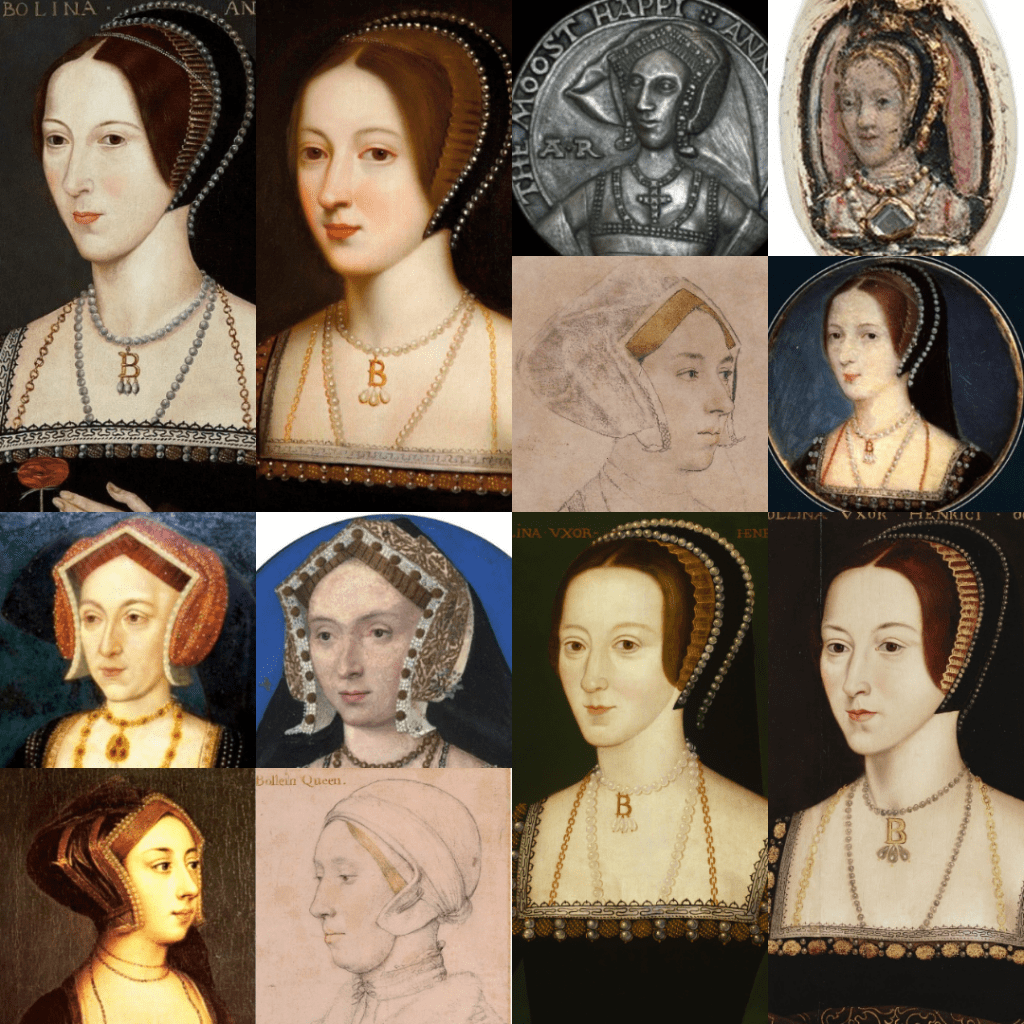

Various sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artworks depicting Queen Anne Boleyn. Only the grey portrait medal in the top-right corner is a contemporary likeness, and even this image is a reconstruction by artist Lucy Churchill. The sepia sketches by Holbein are possibly of her, as is the circular miniature of her in the center of the image, but these attributions are not for certain.

Leave a comment