I’m back on this blog after a nearly three-month break! The end of my MPhil in Early Modern History at Cambridge was hectic and full of late-night editing, but it’s finally done. A month ago, I got my official grade/mark on the MPhil dissertation, which made up 70% of my final degree grade. While my grade of 74 was quite high for the MPhil, it was, somewhat annoyingly, only one point below the minimum for a Distinction, the highest grade classification at Cambridge. Nevertheless, now that I’m officially done with my Master’s, having graduated just under two weeks ago, I feel that now’s the perfect time to look back on the nine months I spent at Cambridge studying and researching for my MPhil.

A picture of me at my graduation!

I had already visited Cambridge twice when I traveled there once more to start my degree in late September, the second time having been at the end of my BA, right after my final exams finished. Still, two day-trips were hardly enough time to get to know the city or my college for the MPhil, Hughes Hall, adequately, so I already felt somewhat nervous. Moreover, because of my autism, I’ve come to learn over the years that it takes months, if not sometimes a year or two, to truly find my footing in acclimatizing to a new social environment. It is, though, always a bit disheartening whenever, inevitably in my experience, I drift away from most of the friends I make at the start in a new environment.

My first visit to Hughes Hall in June 2024

Still, I did make several friends inside my college, and of course, also in my degree. Given how busy we all were as students of a mature and postgraduate students-only college, I felt very thankful that many dropped by lunch, dinner, and the social events hosted by the Hughes Hall MCR so I could catch up and hang out with them. To be honest, the second category of friends was somewhat inevitable, as there were only eleven other people in the Early Modern History MPhil. Given that we all had to take one class called “Sources and Methods” in Michaelmas Term (i.e. the first trimester), it was vital that I at least got on with them.

Fortunately, given our shared interest in early modern history, as well as their shared and genuine kindness, warmth, and humor, I got on swimmingly with them. In case they’re reading this, I want to give a shout-out to Shreya, Lizzie, Asher, Sacha, Daniel, Freya, Matt, Adele, Isabel, Robin, and Harvey; you were all the best cohort of fellow early modernists I could’ve asked for! I wish I could tell you more about their amazing research that they undertook for this degree, but those are their stories to disclose.

So, leaving aside my social life, what were the classes in my MPhil like? I took four classes in Michaelmas Term, only two in Lent Term (i.e. the second trimester), and none at all in Easter Term (i.e. the final trimester). Although, thankfully, I didn’t have to write weekly tutorial essays like in my Oxford BA, this absence was due to a shift in teaching mode. While both Oxford and Cambridge mainly teach undergraduates in two-on-one tutorials (or supervisions, as the latter labels them), Master’s students, at least for history, are taught in bigger classes with six to twelve people.

Two of these four classes were not for my degree, but both instructed me in important skills for my journey as an early modern historian. They were a paleography (i.e. study of old handwriting) class offered by the wonderfully lively Dr. Andrew Zurcher from the English Faculty, and a Latin class offered by the Cambridge University Language Center. I found both immensely enjoyable and useful. I spent hours every week both in and out of the classroom examining and reading old documents, translating Latin passages, and trying to get to grips with declension charts. To be sure, I did (and still!) find parts of Latin painful, but I manage to push through by reminding myself of just how important it is to be fluent in Latin as a historian of early modern Europe.

One of the transcriptions of early modern documents I turned in for the paleography class; apologies for my awful handwriting!

I took three classes for my degree proper. In Michaelmas, I took the Core Course for the MPhil, Sources and Methods, along with an Option Module on the history of early modern books. Both of them, along with my second Option Module in Lent Term, were assessed by essays of 3,000-4,000 words, each worth 10% of my final degree mark. Because of the possibility that the History Faculty might repeat the questions I chose under different wording for next year’s MPhil students, I unfortunately can’t reveal what I wrote on. I can say, however, that researching and writing essays of that length, longer than any tutorial essay I’d ever written for my Oxford B.A., helped me significantly with the final challenge of writing my dissertation.

Every week in Sources and Methods, we looked at a different theme or topic in the study of early modern history, such as images, belief, or objects, read around 150 pages, and then engaged in a group discussion. Thinking critically each week at the start of my MPhil about important methodological questions, such as what sources historians can use to reconstruct early modern beliefs, really helped me develop my own thinking and analytical skills as a historian. The History of the Book class was somewhat different, as our tutor mostly brought in early modern books from the Perne Library at Peterhouse. He thus prompted us to notice material factors about these works that I’d never thought to look at before, like their signature marks or how they were actually made. Finally, in Lent, I took perhaps my favorite class of the three: Absolutism, Monarchism, and State-Formation in Early Modern Britain and Europe. Admittedly, I didn’t read all of the assigned readings for every week, particularly as my research for the dissertation ramped up and the weeks progressed. Nevertheless, I enjoyed breaking down such complex topics in political history, one of my comfort fields, into its components, both intellectual and conceptual. Perhaps my favorite week in this class was the last one, where we discussed ceremonial and ritual and how it bolstered (or failed to support) absolutism, monarchies, and state formation, such as in coronations and court etiquette.

A snippet of the voluminous notes I took for the Absolutism class

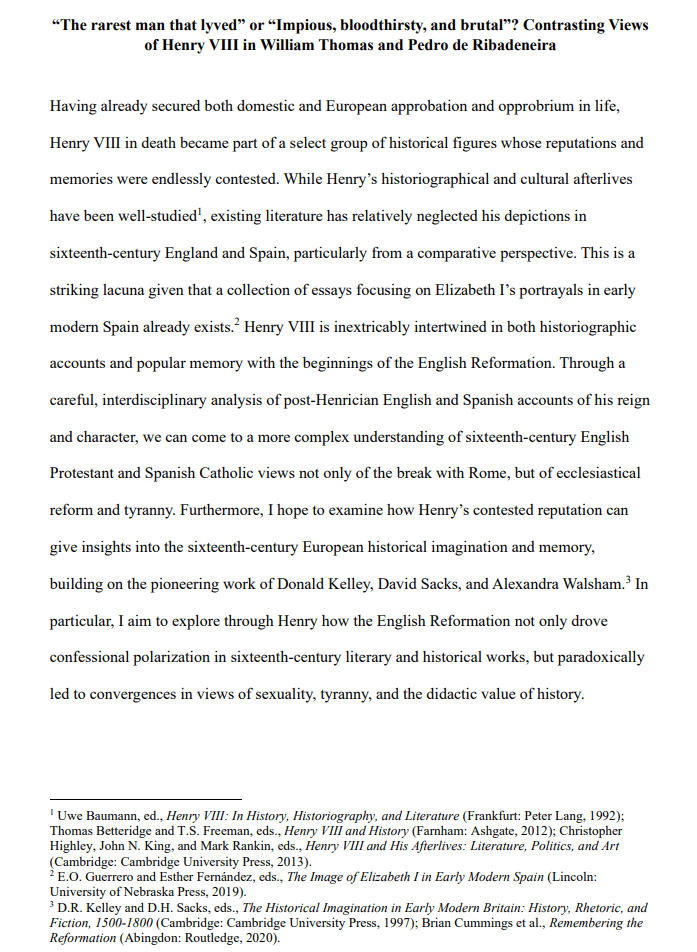

It’s now time to talk about the dissertation. To be frank, I’ve struggled with writing this section. For nine months, it was an inescapable part of my life, first as a looming, intimidating prospect just over the horizon, and then as a set of deadlines to work towards. As part of my MPhil application to Cambridge, I had to submit a research proposal which outlined my research, why it was necessary, what historiographical gaps I’d fill, and what sources I’d use. I was on my summer break from Oxford, in between the second and third year of my undergrad, when I sat down and came up with what my MPhil research would focus on. It took me less than an hour to come up with a topic, probably because I knew I wanted to do something related to Henry VIII and his reign. After all, my BA thesis was focusing on Anglo-Spanish diplomacy under Henry from 1509 to 1536. Would it be a good idea to also use my fluency in Spanish to research another Anglo-Spanish topic relating to him? I decided it would be.

The start of my Cambridge MPhil research proposal

As for why I chose to focus on the Edwardian (i.e. reign of Edward VI) Welsh Protestant writer William Thomas and a Spanish Jesuit historian under Philip II, Pedro de Ribadeneyra, I was struck by how, despite their substantial accounts of Henry’s life and reign, very few Anglophone historians had examined them in any detail. Moreover, fewer still had looked beyond noting their overall takes on Henry to connect their works to broader intellectual and cultural trends and discourses around important topics like masculinity and ideal kingship. And no one, as far as I could find, had compared them jointly to draw these connections out. Admittedly, the proposal itself was far from perfect. I was vague on what issues I’d actually focus on, as I wasn’t sure myself, and what the theoretical/methodological bases for my dissertation would be. Still, the esteemed Professor Alexandra Walsham kindly agreed to prospectively supervise me if I got in, which I promptly did.

Once I started my MPhil, the four classes I had in Michaelmas, along with the required readings and homework, made it impossible for me to engage with the dissertation as much as I wanted to. Fortunately, I was able to start my research and meet with my supervisor almost from the beginning. Professor Walsham is, in addition to being a Commander of the British Empire (CBE), former Chair of the History Faculty, former Vice-President of the Royal Historical Society, and a renowned historian of early modern British religious and cultural history, one of the kindest and hardest-working academics I’ve ever met. I truly can’t thank her enough for her constant guidance and reassurance throughout the MPhil, valuable pointers, ability to make the time in her schedule to leave copious and detailed feedback on my dissertation drafts, and above all, helping me push the boundaries of my skills in historical research and analysis.

Within a month of starting the MPhil, and soon after our first meeting, I started reading and taking notes on as many pieces of secondary literature as I could get my hands on. Previous monographs on both Thomas and Ribadeneyra, past scholarship on sixteenth-century English and Spanish views of ideal kingship, gender roles and sexualities, and religion, and books on historical memory and early modern English uses of history – I read it all. I aimed to get all of my secondary sources done before I started analyzing my primary sources and writing the dissertation to provide an analytical framework for the latter. However, I ended up having to read additional monographs and articles in the process of writing and revising the dissertation, an object lesson if ever there was one in how important it is to be flexible with your routine and priorities when engaging in scholarship.

Part of my original list of secondary sources for my dissertation research

My primary sources were, naturally, Thomas and Ribadeneyra’s accounts of Henry’s life and reign, as found in the former’s 1547 manuscript dialogue Peregryne and the latter’s 1588 ecclesiastical history Historia Ecclesiástica del Scisma del Reyno de Inglaterra (“Ecclesiastical History of the Schism of the kIngdom of England”). I didn’t, however, forget to contextualize their accounts with the help of works written by their co-religionists, such as Edward Hall for Thomas and Nicholas Sander for Ribadeneyra. Looking back on this dissertation with a more critical eye, I do somewhat regret using Spencer Weinreich’s annotated English edition of Ribadeneyra’s work as my base text. While I did cross-check it against the original 1588 Spanish text of the Historia, and it was quite a faithful translation, I am fluent enough in Spanish that I could have read it in the original, with Weinreich serving as a guide rather than the main text. I still stand, however, by my decision to use the critical edition offered by Ian Christopher Martin in his 1999 PhD thesis as the base text for my analysis of Peregryne, as it contains a robust apparatus of textual variations.

Once I finished my research, it was time to start writing my dissertation. I found it very helpful that I’d already written a 1.5-page outline of what I wanted to argue in my dissertation in Michaelmas. This allowed me to break up otherwise daunting swathes of writing, like the main chapters, into manageable chunks that I could divide up per day to create an intensive yet manageable routine for myself. Moreover, to not hinder the mental flow of my writing and analysis, I left proper footnoting and citations until the end. While I did make footnotes where I noted the author’s name, book/article name, and page number, these were not properly formatted or styled. This way, I had enough information for myself to be able to do the hard work of formatting them according to the Faculty’s style guide once I was done with the first draft.

In my dissertation, I argued that both Thomas and Ribadeneyra, shaped by a tense atmosphere where both they and their kings sought to respond to the English Reformation, portrayed Henry VIII’s life in an exemplary, didactic fashion. Whether seeking to encourage the Tudor state’s fervent implementation of Protestant reform or Spaniards’ material and spiritual support for the Armada, Henry’s life and reign became a collection of either positive or negative moral exempla, designed to instruct their audiences in virtue. While Thomas presented Henry as an exemplary monarch, man, and believer, marked by good governance, masculine self-control, and enthusiasm for Protestant reform, Ribadeneyra excoriated him as an impious heretic, bloodthirsty tyrant, and an ‘effeminate’ captive to his carnal urges. To accomplish this, both used additional exempla from English history, appeals to primary sources, and elision of the facts of his reign that complicated their argument. Their works were not just serious depictions of Henry VIII but notable additions to sixteenth-century political, social, and religious discourses.

However, both Thomas and Ribadeneyra’s depictions of the late king were complicated by areas of authorial anxiety and even cross-confessional ideological convergence. Thomas often expressed worry, if not fury, about Catholic accusations of Henrician tyranny, while both he and Ribadeneyra glossed over notable aspects of his reign. Still, their basic agreement over the existence of a dichotomy between good kingship and tyranny, suspicion of female charms, and condemnation of feminine adultery indicates the continued existence of a shared conceptual culture around ideals of both governance and femininity in sixteenth-century Western Europe.

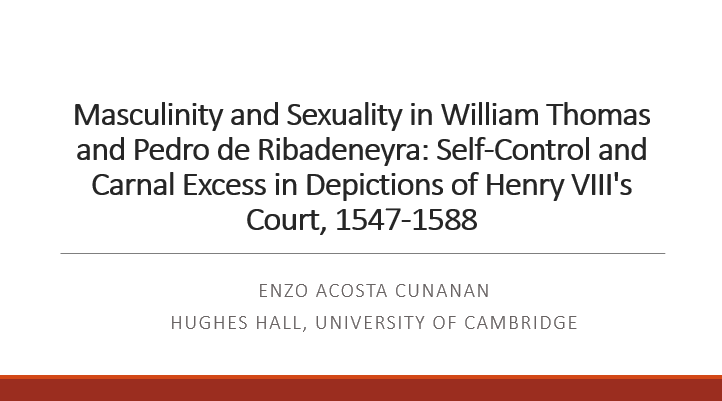

Finally, it was time to submit the dissertation. I ended up being quite thankful that I could submit it an unlimited number of times before the deadline on June 11, as every time I submitted, I ended up finding more typos that hadn’t been caught by spellcheck. Fortunately for my sanity, the deadline finally came and went, forcing me to stop revising it. This also allowed me to get it properly bound by J S Wilson & Son Bookbinders, who did a brilliant job making the dissertation into three beautiful mementos for myself and my family. I even got to present part of my research at the postgraduate Cambridge Workshop for the Early Modern Period at the end of the year, offering me valuable experience in presenting my research and answering questions! If you want me to send over either the PowerPoint or the MPhil dissertation document itself, drop me an email at enzoacunanan@gmail.com!

The first slide of my WEMP PowerPoint

Eventually, the final grade came somewhat earlier than expected, on July 9; as I said above, it was a 74. One of the anonymous marker’s comments stuck out to me when I read the feedback report. It said that while my dissertation was convincingly argued, it offered few surprises in its conclusions. Perhaps that’s why I ended up getting just below a Distinction. Maybe I hadn’t been original enough in my thinking and analysis, leading to truly new conclusions. It’s something I aim to remedy for my doctoral research, and I’ll seek to flex the historical analysis part of my brain as much as I can.

But despite the minor disappointment of my final grade, I am still very, very thankful to have gotten the opportunity to do my MPhil at Cambridge. To paraphrase a post I made on my Instagram, the Latin motto of Cambridge translates to “From here, [we draw] light and sacred draughts.” While certainly true in my case, I drew so much more. I drew friends and memories for life, even more knowledge about early modern history, and most importantly, the skills needed for my DPhil at Oxford this October.

Leave a comment